Within the walls and abandoned buildings of New York, well-known for its ever-changing landscape, natives of New York are being pushed out of their neighborhoods through gentrification. There is a common factor; developers and name-brand companies target the art, and not the art collecting dust in grandma’s attic — graffiti and street art.

Graffiti became “this actual weird dialogue going on in real time on the street,” said Randy Kennedy, a journalist who writes on art. Graffiti quickly evolved as individual “writers,” as the graffiti artists are referred to, put their own technique and style in their writing.

What was once considered trashy and disturbing, was now recognized as culture, with depth. Developers and local property owners are aware of the opportunities that culture brings. Instead of renting out spaces to viable small business owners and artists, these local owners patiently wait for big money renters to take interest.

“There are storefronts that will remain empty for a long time that used to have family-owned local businesses,” said Kennedy. “And the people who own those storefronts hold out until they get Starbucks.”

As property values go up, those usually affected by gentrification are families of color, artists, and the working class, forced to find different neighborhoods to claim as their own.

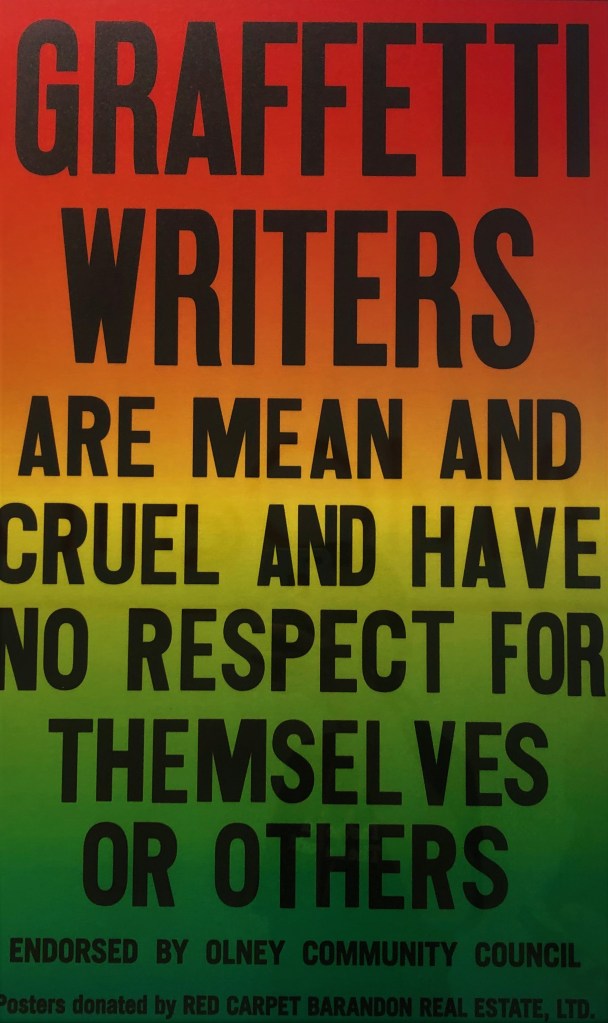

Graffiti did not begin on the streets of New York, but many New York artists quickly claimed their own style of writing. Graffiti evolved into a culture with terms, crews, and territories. Despite being considered vandalism, which is illegal, graffiti became an outlet for many people to express themselves, mark their territory, and add something to their community.

Graffiti can be done through tags, stickers, symbols, and throws. Tags are a stylized name or symbol; stickers are placed everywhere with various methods of glue; symbols may represent a name or something unique to the writer, and throws are a larger pieces consisting of multiple colors that work together. Through these variations, graffiti becomes communication.

It is an extremely competitive art form, according to Fales. Different territories and cities will compete over each other’s work until the dispute dissipates or the artwork is so impressive it is considered a victory.

“If it was really good, people wouldn’t tag on top of it,” said Kennedy. “You’d see people would tag low on it, but then they would stop because they just didn’t want to put paint on top of that.”

“Graffiti has an accent,” said Michael Fales, a graffiti documentarian. He added that different cities have different styles; some cities’ writing is illegible to visitors, and some are identifiable even to the untrained eye.

Graffiti has been a significant part of not only New York, but many cities such as Philadelphia, Chicago, and L.A. Now, graffiti is being claimed by large corporations that are taking over these cities in the form of advertisements and merchandise.

“Half the time you don’t know if it’s graffiti or not,” said Helene Stapinski, a freelance journalist and New York local for much of her lifetime. “It’s very disturbing, so you don’t want to look at the graffiti anymore because you’re like, ‘Wait a minute, maybe I’m being duped, it’s Adidas or Nike.’”

As graffiti is washed away and murals are pasted over the city’s landscape, some feel that the process of gentrification is being ignored, with commissioned murals acting as an agent for the change.

“In a neighborhood like Bushwick, it was a neighborhood of artists, and that’s why graffiti started there to begin with,” said Stapinski. “Now the real estate people have moved in and said, ‘Look, this is where the artists live, let’s build condos,’ so then all the artists get pushed out. It’s very depressing.”

As New York’s crime goes down and condos go up, the city becomes a more desirable place to live for people in the higher class, leaving less room for the artists who made the streets desirable. Gentrification is being disguised as “becoming a community,” one that supports artists rather than exploits them.

“By slapping a mural on the facade, developers can increase a property’s appeal,” said Zach G. Cohen in his article, Graffiti and Gentrification in Brooklyn. “Giving hopeful residents the sense that they’re not taking part in changing the local landscape, but rather joining a community whose character has been developing on its own.”

As organizations, such as the Bushwick Collective, use their influence to commission murals on walls that once contained graffiti, new residents are made to feel included in the art that decorates their walls. If the demand for well-known corporations and clean commissioned art was not present, developers would have no reason to pursue it.

“You can be in certain parts of Paris and it still feels very much like a block is not corporately owned,” said Kennedy. “I think if New York is going to keep that flavor, there probably has to be some intervention from the city, because if you just allow the market to take its course, eventually, it’ll just be a Starbucks on every corner—which is really sad.”

Originally written July 4, 2019.