the finding hope project

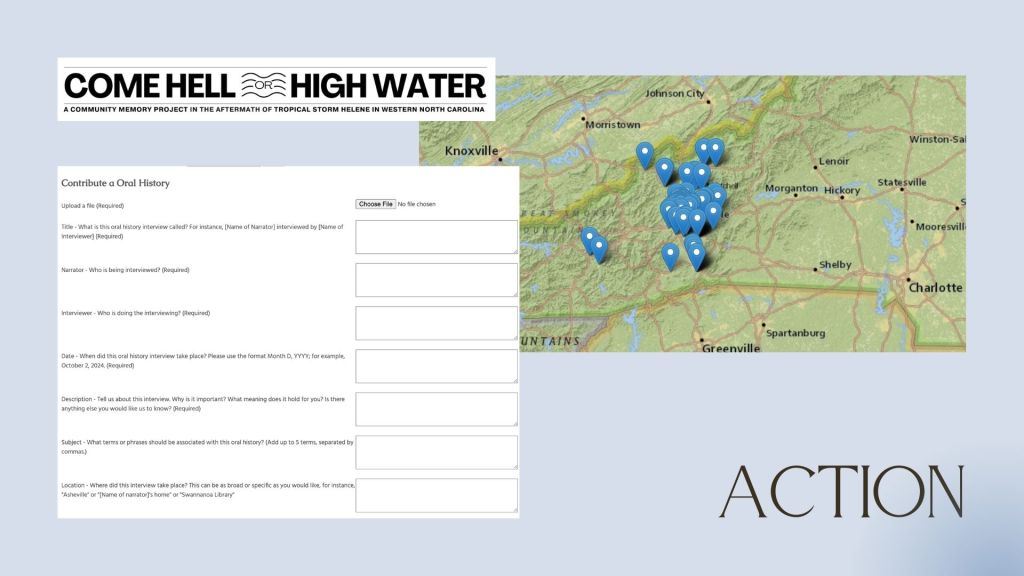

An independent oral history project dedicated to uncovering how the residents of Western North Carolina were impacted by Hurricane Helene. This research will also be publicly accessible through Buncombe County Special Collections’ community memory project Come Hell or High Water.

This research has been presented at UNC Greensboro’s 2025 Webinars Worth Watching event where it received a People’s Choice Award; and presented at UNC Chapel Hill’s 2025 LAUNC-CH conference.

More images are available on the photography page.

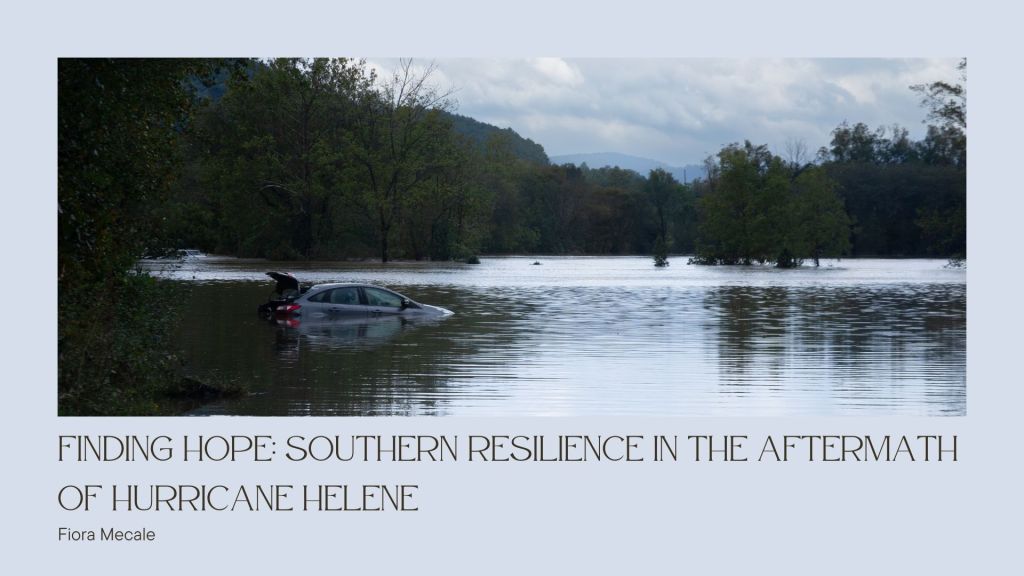

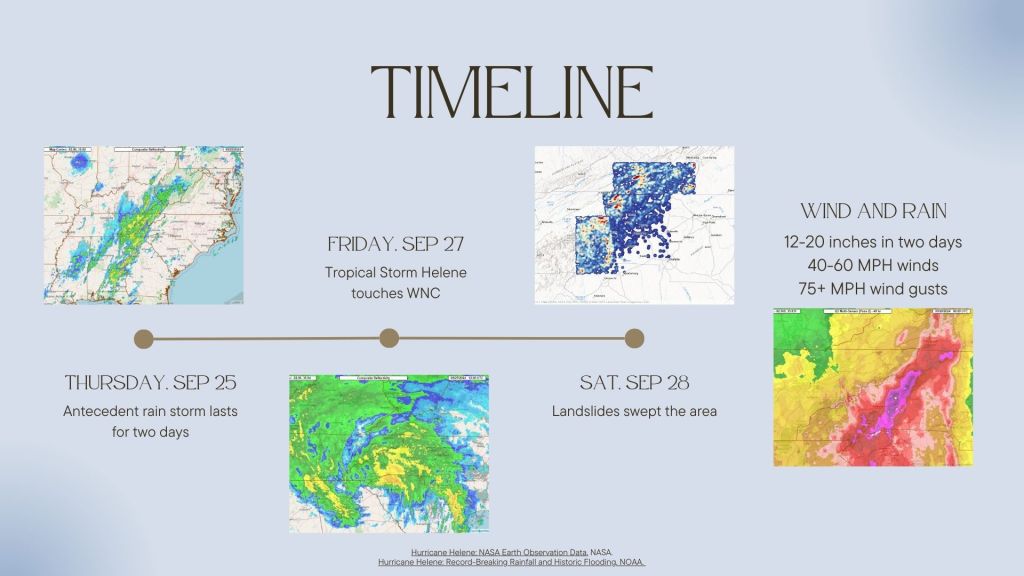

On a Wednesday in September, I prepared to leave work as whispers began floating about the Hurricane down South. It had already been raining here for days. Creek beds were beginning to rise, and someone warned me we might get hit like Hurricane Katrina. Work was canceled for the next two days as emergency alerts began coming in on phones. On Friday afternoon, I drove a block away from my apartment and saw the flood level rise above neighborhoods, stores, and cars. I turned to my partner and said, “How many once in a lifetime experiences will our generation have?”

Word of mouth became our primary form of contact, the occasional phone call if both people got lucky. Nothing could match the relief of the other person picking up the phone, alleviating the dread of possibility. I had seen my hometown flood and knew other areas were likely worse. I felt this intense urge to do anything I could. Supplies came flooding in, resource centers were overwhelmed with volunteers. But there was one thing I did not see happening amid the chaos—the preservation of what had happened.

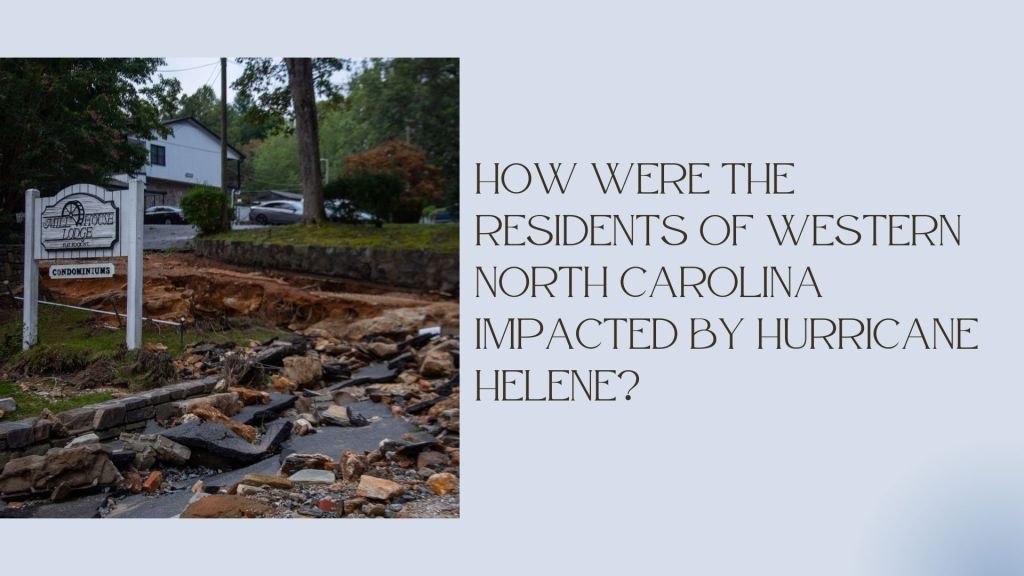

By the time service returned and I could contact my instructor again, I told her I didn’t think my original plan to do a research assignment on Scholastic Book Fairs was going to work out. She told me to continue documenting instead. So, I sought to answer, How were the residents of Western North Carolina impacted by Hurricane Helene? I decided to answer this question by collecting oral histories. But we were still all in crisis. Every street I went down, every person I spoke to, was a reminder that my home would never be the same. To ask people to tell me their stories felt invasive and selfish. In the beginning, I was restricted by a shortage of gas and blocked roads. I started by interviewing within proximity and later began traveling to collect interviews. One of my early interviews was with a family member, Ally.

Although I had seen Ally many times prior to this interview, I learned so much from coming to her with specific questions. She shared with me how she braided a spell into her hair the night before the storm. When the storm began around four in the morning, the lightning was so bright it lit up the entire room. It looked light the room was on fire. For the next month, she had a hard time sleeping. She was already used to restless nights, but this was different. There was a heaviness this time, weighing her down each night, in the dark, reminding her how much was out of her control. And it was hard to fall asleep for a long time. One of my routine questions for each interview is, “Did you lose anything in the storm?” at first, Ally laughed and said she lost hope, but later asked to go back to that statement and added,

“I think that I said hope, but I don’t mean that. I think that after this I really got a lot of hope watching everyone come together and try to be a community and try to take care of each other.

It gave me more hope.”

When I first began this project as a research assignment for school, I did not anticipate what it would become. It began as a way to help my community in the only way I knew how. However, each of the seven interviews I have conducted finished with gratitude. Each one began with a statement from them to diminish their experiences, expressing that they didn’t think they had much to say. Most of who I’ve spoken to were not first responders, they were not rescued by a helicopter or from a landslide. They were people who made it out alive, one way or another, and found the wreckage in the days to come. No matter the story, they never thought theirs was important. By taking the time to sit with them, and sometimes drive hours, they were changed. They seemed lighter by the end, as though just in listening to them I had helped them remove this massive weight they were unaware they had been carrying. I was interviewing them, but from their perspective, I was validating what they had been through. I was present with them while they shared their testimonies, and this experience changed me too.

I thought oral history collection was a convenient method of preservation, but it became more than that in these homes. Me listening to their stories offered them healing, and it offered them hope.

I hope this project offers you something, as well.

This slideshow presentation represents what has been used for presentations of this research.